The Finacial Protection Gap

The following was my contribution to California’s Fifth Climate Change Assessment.

Globally, over the last three decades, economic losses associated with weather-related extremes have risen significantly.[1] California is no exception. The 2022-2023 winter storms cost an estimated $4.7 billion in losses, much of it along the Central Coast (NOAA National Centers for Enviornmental Information (NCEI), 2025). The Pajero River levee collapse put an estimated 5,895 residential structures at risk, with a combined reconstruction value estimated at $2.88 billion (Wells, 2023). As the frequency and severity of extreme events continue to grow, the sobering impacts are now shaping the lives, livelihoods and futures of thousands of Californians. Research conducted by the insurance industry finds that socioeconomic factors, such as coastal development, ageing infrastructure, and increased building replacement costs are making households less resilient to natural disasters and other economic shocks (Banergee et al., 2024).

While disaster mitigation and prevention have long been key components of disaster management, a crucial missing element is a strong emphasis on post-disaster recovery and the resources needed to rebuild and restore communities after a disaster. The lack of emphasis on post-disaster recovery planning deepens a financial protection gap - the difference between the total financial resources of households, businesses, or communities and the costs of disaster recovery (Jarzabkowski et al., 2023).

The financial protection gap highlights broader issues affecting recovery, including lack of emergency savings, the economic effects of temporary unemployment, and extra costs that may not be covered by insurance, such as housing, healthcare, and relocation expenses. Under-insurance was a significant factor in the 2017 Thomas Fire in Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties. Insurance often did not cover the full extent of losses, especially for damage like mudslides and debris flows that followed, and the recovery process for many victims was challenging, with issues such as slow rebuilding times, contractor fraud, and the need to file lawsuits against the utility for damages not covered by insurance.

The financial protection gap emphasizes the interconnectedness of these various financial vulnerabilities and the importance of developing cohesive strategies to enhance resilience against disasters and ensure effective community recovery (Jarzabkowski et al., 2023). When communities lack adequate disaster recovery resources—whether financial, social, or infrastructural—they struggle to recover, and the economic consequences are prolonged and amplified This creates a cycle of vulnerability, where communities are unable to recover from one disaster before facing another, further widening the existing financial protection gap and hindering long-term resilience. (You, 2024). The resulting financial burden disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, limiting their ability to rebuild homes, businesses, and livelihoods (Kousky & French, 2022).

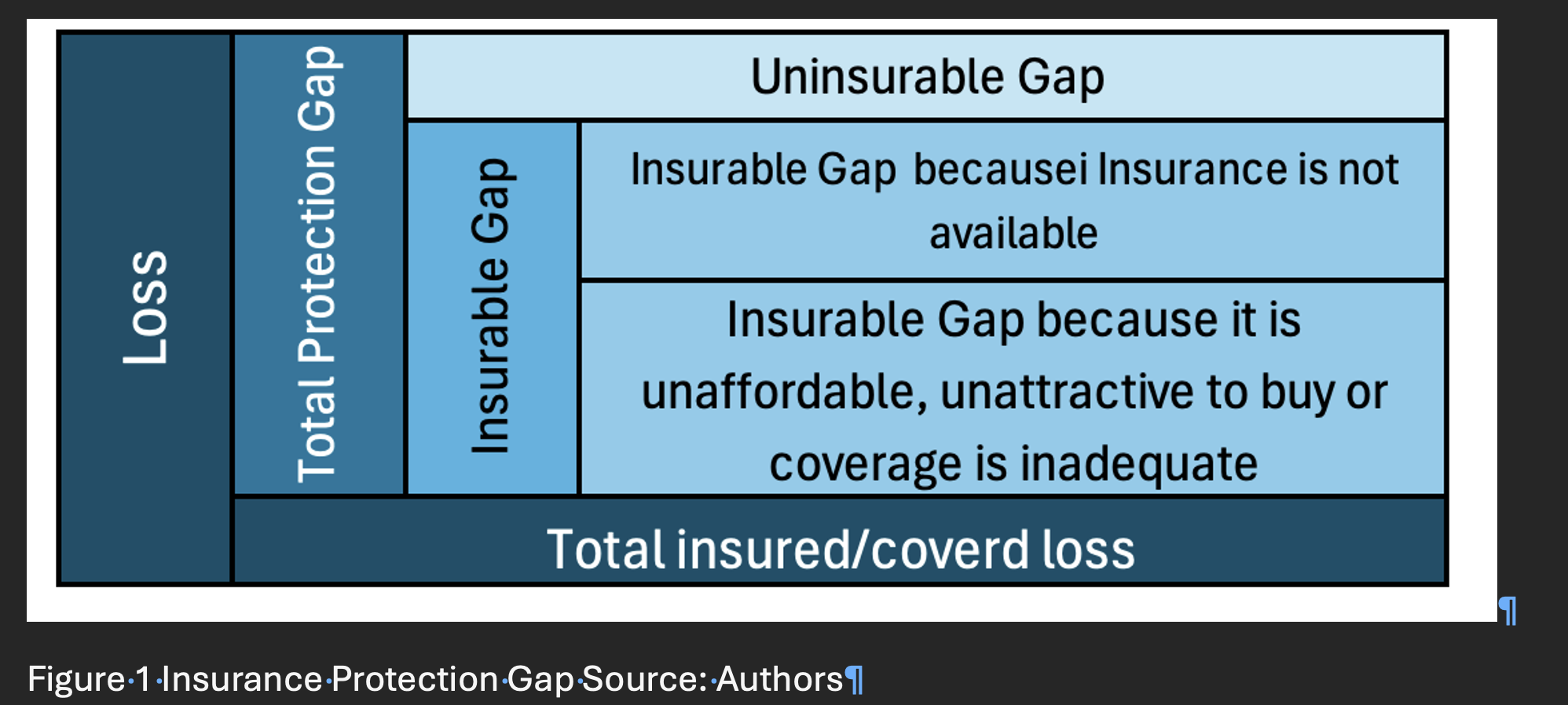

Insurance can be one source of funds to close the financial protection gap. Unfortunately, as climate-caused disasters increase, insurance to cover disaster costs becomes more expensive creating an insurance protection gap - the difference between potential financial losses faced by households and businesses due to climate-related events like flooding and the actual insurance coverage available to mitigate those losses (Jarzabkowski et al., 2019). In California, this gap is becoming increasingly pronounced as traditional insurance models struggle to keep pace with the rapidly evolving risk landscape shaped by climate change. This disconnect not only leaves many Californians financially exposed but also hampers the state's overall resilience to climate-related disasters (Jarzabkowski et al., 2019).

Low-income households face unique post-disaster financial challenges, including increased financial strain, reliance on external aid, and worsening social inequalities (Rhodes & Besbris, 2022). The protection gap affects vulnerable populations differently. Mothers, often the primary family caretakers, face the added stress and burdens of managing the family’s recovery (Kimbro, 2021). Elderly and disabled individuals face increased healthcare costs, further straining their finances (Lowe et al., 2013). Undocumented households face an additional layer of vulnerability, as their fear of deportation prevents them from accessing essential aid programs and forces them to depend on limited community support (Méndez et al., 2020). This fear influences their decisions regarding evacuation, sharing information, and applying for assistance, thereby widening the financial protection gap and underscoring a gap in the provision of equitable and accessible recovery resources for all including long-term financial support, preventative measures, and policies that address systemic inequalities.

Although these gaps disproportionately affect low-income households are disproportionately affected by the protection gaps, high-wealth individuals and local governments are not immune. High-wealth households may encounter considerable financial losses which can disrupt their financial planning. Additionally, the broader community suffers from prolonged economic stagnation, diminished viability for local businesses, and increased strain on public services.

[1] Economic losses combine insured and non-insured losses, including financial losses directly attributable to a major event. Insured losses are a subset of losses paid by commercial or government schemes.

The protection gap can also affect entire communities, and the repeated impact of disasters on communities can lead to a phenomenon known as "disaster recovery gentrification," a phenomenon similar to green and climate gentrification. (Lambrou et al., 2025). Although recovery processes are essential for rebuilding, well-intentioned recovery resources can include barriers that low-income households often cannot overcome. In addition, areas may be redeveloped in ways that price out original residents, further marginalizing vulnerable populations. This unequal distribution of risk and recovery capacity widens existing socioeconomic gaps and undermines the overall resilience of the region.

The Central Coast is particularly vulnerable to financial protection gaps that can threaten entire communities and worsen existing social and economic inequalities. Low-income households, communities of color, and immigrant populations often live in areas that are more susceptible to natural hazards due to historical patterns of discrimination and limited housing options.(Holzheu & Turner, 2018) These communities typically have fewer financial resources to invest in protective measures, such as home hardening against wildfires or elevating structures in flood-prone areas. When disasters strike, they are less likely to have adequate insurance coverage or savings to recover from losses, forcing them to rely on limited government assistance or go into debt (Collier & Kousky, 2024). Moreover, vulnerable groups may encounter additional barriers in accessing recovery resources, including language obstacles, lack of documentation, or limited technological literacy to navigate complex aid application processes. The aftermath of extreme climate events can also lead to displacement, job losses, and health issues, further entrenching cycles of poverty (Cutter et al., 2009; Lowe et al., 2013).

As natural disasters grow more frequent and severe, many property owners and businesses are likely to be underinsured or lacking adequate coverage, leading to substantial uncompensated losses (Holzheu & Turner, 2018). In Santa Cruz County, a 2024 Santa Cruz Grand Jury (2024) report found that the county agencies' lack of an effective disaster response plan before the CZU Fire led many fire victims to incur unnecessary expenses during the rebuilding process (Santa Cruz County Grand Jury, 2024). Notably, three and a half years after the CZU Lightning Complex Fire, less than a third of all homes had been rebuilt, and the obstacles to recovery and rebuilding continue to plague and frustrate the fire victims, the majority of whom were either uninsured or underinsured. When insurance payouts were finally made, funds were insufficient to cover the cost to rebuild.

The financial protection gap created by increasing flood and wildfire events can create a cascading effect on the Central Coast economy. Property damage and business interruptions can lead to decreased property values and reduced economic activity, which in turn diminishes the tax base for local governments. With lower tax revenues, municipalities often struggle to maintain and improve essential public services, including emergency response capabilities. Furthermore, the persistent threat of disasters can deter new investments and drive existing businesses to relocate, further eroding the economic fabric of Central Coast communities. Small businesses are particularly vulnerable to these disruptions and may face permanent closure following significant losses. Economic instability and diminished resources impede a community's ability to invest in necessary

To address the financial and insurance protection gaps on the Central Coast local and regional governments can create a Protection Gap Entity that brings together different insurance, government, and intergovernmental stakeholders in efforts to address these gaps (Jarzabkowski et al., 2023). Such an entity can serve as a pivotal step in orchestrating a multi-faceted approach to financial resilience, leveraging diverse stakeholder expertise and resources to develop innovative solutions tailored to the region's specific needs. An example is the California Earthquake Authority. Originally established to provide earthquake insurance, in 2020 it was expanded to administer the California Wildfire Fund.

A key role of a Protection Gap Entity is to keep disaster risk insurable. While crucial for recovery, insurance is a "Goldilocks" arrangement: effective only when flood risks and losses fall within a manageable range of frequency and severity and if there is adequate demand to spread the losses (Kousky, 2022). A risk-layering approach, which combines different risk-financing tools according to the frequency and severity of the shocks (World Food Programme, 2023), can contribute to keeping risk insurance affordable. Figure 2 illustrates the risk layering approach where small, frequent losses are managed with reserves. As losses become more frequent and more severe, they are managed with a contingent credit approach. Finally, losses that are infrequent but severe are managed with insurance. Reserving insurance for only those losses that exceed the immediate financial resources keeps insurance affordable. Other strategies—risk reduction, risk retention, or calculated risk-taking are also important (Figure 2). Providing access to innovative financial services that promote risk reduction and adaptation (Jarzabkowski et al., 2023; Schanz, 2018; World Food Programme, 2023) encourages prudent risk-taking by assisting households and communities in accessing credit and other forms of capital to finance adaptation and risk reduction and risk transfer.

Importantly, Protection Gap Entities can also catalyze innovative insurance and financial solutions to address climate-related risks. These may include parametric insurance, which offers expedited payouts based on predefined environmental triggers, public-private partnerships that can facilitate the development of novel financial instruments such as resilience bonds, and community-based insurance pools to more equitably distribute risk and enhance coverage accessibility for vulnerable populations.

Actions to address the financial protection gap on the Central Coast can involve a greater emphasis on disaster recovery planning beyond just insurance. This could include establishing dedicated disaster recovery funds, implementing tax incentives for property owners who invest in resilience measures, as well as microfinance initiatives and low-interest loan programs that provide critical support for small businesses and low-income households who undertake protective retrofits. Additionally, updating land-use policies and building codes can discourage development in high-risk areas and promote resilient construction practices.

As climate change results in increased sea-level rise, more frequent wildfires, and increased flood risk, the families and businesses in California's Central Coast will be presented with significant challenges. Collaborative and innovative approaches, possibly centered around the establishment of dedicated Protection Gap Entities such as the California Wildfire Authority, have the potential to foster novel financial arrangements, promote risk reduction strategies, and ensure equitable access to resources.

References:

Banergee, C., Bevere, L., Gabers, H., Grolimund, B., lechner, R., & Weigel, A. (2024). Sigma: Natural catastrophes in 2023: Gearing up for today’s and tomorrow’s weather risks. Swiss Re Institute. https://www.swissre.com/dam/jcr:c9385357-6b86-486a-9ad8-78679037c10e/2024-03-sigma1-natural-catastrophes.pdf

Climate Change Working Group. (2021). Protecting communities, preserving nature and building resiliency. Department of Insurance.

Collier, B., & Kousky, C. (2024). Household Financial Resilience After Severe Climate Events: The Role of Insurance; https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4857411

Cutter, S. L., Emrich, C. T., Webb, J. J., & Morath, D. (2009). Social vulnerability to climate variability hazards: A review of the literature. Final Report to Oxfam America, 5, 1–44.

Holzheu, T., & Turner, G. (2018). The natural catastrophe protection gap: Measurement, root causes and ways of addressing underinsurance for extreme events. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 43, 37--71.

Jarzabkowski, P., Chalkias, K., Cacciatori, E., & Bednarek, R. (2023). Disaster insurance reimagined: Protection in a time of increasing risk. Oxford University Press.

Jarzabkowski, P., Chalkias, K., Clarke, D., Iyahen, E., Statmueller, D., & Zwick, A. (2019). Insurance for climate adaptation: Opportunities and Limitations. www.gca.org

Kimbro, R. (2021). In too deep: Class and mothering in a flooded community. University of California Press.

Kousky, C. (2022). Understanding Disaster Insurance: New Tools for a More Resilient Future. Island Press.

Kousky, C., & French, K. (2022). Inclusive insurance for climate-related disasters: A roadmamp for the United States. CERES Accelerator.

Lambrou, N., Kolden, C., & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2025). Disaster recovery gentrification in post-wildfire landscapes: The case of Paradise, CA. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 118, 105235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105235

Lowe, D., Ebi, K. L., & Forsberg, B. (2013). Factors Increasing Vulnerability to Health Effects before, during and after Floods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(12), 7015--7067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10127015

Méndez, M., Flores-Haro, G., & Zucker, L. (2020). The (in) visible victims of disaster: Understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and indigenous immigrants. Geoforum, 116, 50--62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.07.007

NOAA National Centers for Enviornmental Information (NCEI). (2025). US billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. https://doi.org/10.25921/stkw-7w73

Rhodes, A., & Besbris, M. (2022). Soaking the middle class: Suburban inequality and recovery from disaster. Russell Sage Foundation.

Santa Cruz County Grand Jury. (2024). Victims of the CZU Wildfire—Four Years Later. Santa Cruz Grand Jury. https://www.santacruzcountyca.gov/Portals/0/County/GrandJury/GJ2024_final/2024-6_CZU_Report.pdf

Schanz, K.-U. (2018). Understanding and addressing global insurance protection gaps. Geneva Association and International Association for the Study of Insurance.

Strategic Growth Council. (2022, July 5). Strategic Growth Coucil Lauches Development of Community Resilience Centers (CRC) Program. https://sgc.ca.gov/news/2022/07-05.html

Wells, K. (2023). Slew of California homes at risk following Pajaro River levee breach: CoreLogic. https://www.reinsurancene.ws/slew-of-california-homes-at-risk-following-pajaro-river-levee-breach-corelogic/

World Food Programme. (2023). Linking disaster risk financing with social protection. World Food Programme. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000150130/download/?_ga=2.46244583.1125709430.1738457906-892610038.1738457906

You, X. (2024). Improving Household and Community Disaster Recovery: Evidence on the Role of Insurance. Journal of Risk & Insurance, 91(2), 299–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jori.12466